However, less than ten years later, Jean de Carrouges and Jacques Le Gris engaged in a well-publicized battle to the death on a field in Paris. In the nonfiction book The Last Duel from 2004, Jager detailed the breakdown of the friendship between the former friends as well as the lady and rape claim at the heart of the argument.

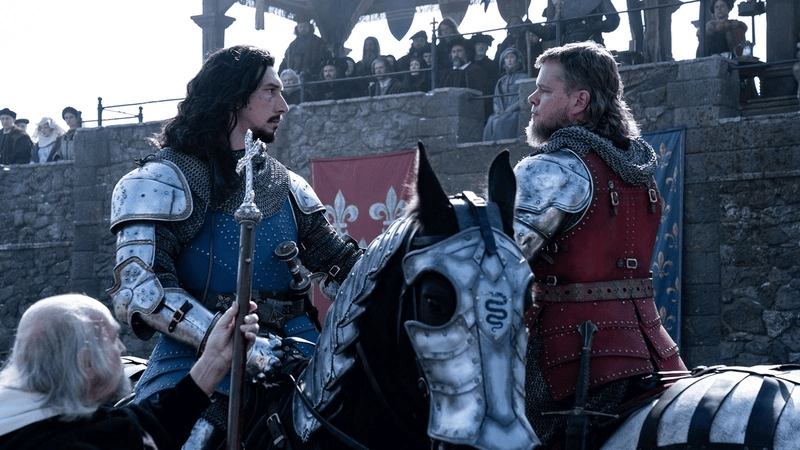

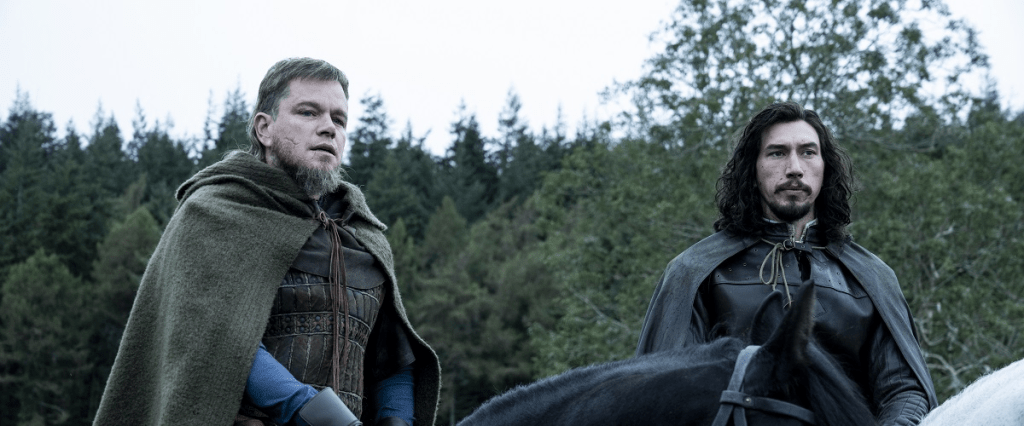

Now, a hugely successful movie by the same name is based on the true story of the 1386 trial by battle. The film, which was directed by Ridley Scott, stars Matt Damon as Carrouges, Adam Driver as Le Gris, and Jodie Comer as Marguerite, Carrouges’ second wife.

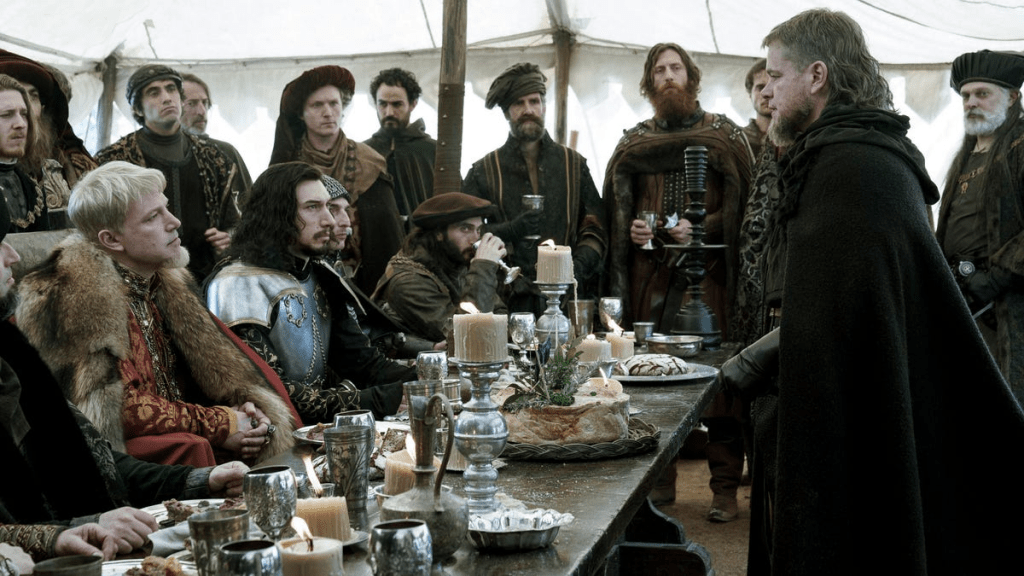

In addition to starring as a feudal lord and friend of both the principal protagonists, Ben Affleck also co-wrote the script with Matt Damon and Nicole Holofcener.

Carrouges and Le Gris kept a wary eye on one another on December 29, 1386, in front of a multitude that King Charles VI of France was presiding over. Watching from the sidelines, Marguerite, who had accused Le Gris of raping her, was acutely aware that her husband’s defeat would be seen as evidence of perjury, vindicating her attacker and ensuring her execution by burning at the stake for the crime of bearing false witness. She was dressed entirely in black.

In the moments before the battle, Carrouges remarked to Marguerite, “Lady, on your evidence I am about to chance my life in combat with Jacques Le Gris.” You are aware of the justice and truth of my cause. My Lord, it is as you say, and you can battle with confidence because the cause is just. Le Gris’ trial by fight therefore got under way.

Before The Last Duel opens on October 15, here is all you need to know about the real history behind it, from the rules of trial by combat to the punishment of sexual abuse in mediaeval society. Spoilers follow.

Who participates in The Last Duel?

A brief introduction to mediaeval France The king, who received guidance from his royal council, the Parlement of Paris, was at the top of society. Barons, knights, and squires made up the three basic classes of aristocracy beneath him.

In addition to owning land, barons like Affleck’s character, Count Pierre d’Alencon, frequently served as feudal lords, giving vassals—a phrase for any man sworn to serve another—property and protection in exchange for their services.

Squires were one level below knights, but individuals in both classes frequently worked as vassals for overlords who held higher positions. (Le Gris and Carrouges first served the Count Pierre as squires and vassals, but Carrouges was knighted in 1385 for his military service.) Warriors, priests, and workers were at the bottom of the social scale and had few political rights or sway.

Does The Last Duel have a real-life basis?

Simply said, absolutely. As they portray Marguerite’s rape and the events that followed it from the perspectives of Carrouges and Le Gris, respectively, the first two chapters of the three-act movie, which were written by Damon and Affleck, substantially rely on Jager’s research. (Jager provided comments on the movie’s script, recommending historically appropriate wording and other adjustments.)

Holofcener’s third and final chapter, which is narrated from Marguerite’s perspective, concludes the book. This section “is somewhat of an original script,” as Damon tells the New York Times, “because that universe of women had to be almost built and imagined out of whole cloth.”

The movie version follows the trio’s relationship from its happy beginnings to its bloody conclusion. Following Marguerite’s rape, Carrouges asks the French court to hold a judicial combat trial for Le Gris.

(Jager says that the “ferocious logic of the duel meant that proof was already latent in the bodies of the two fighters, and that the duel’s divinely assured outcome would reveal which man had swore falsely and which had told the truth in a piece for History News Network.)

If Marguerite’s husband loses the duel, “proving” both of them guilty, she will be beheaded as the main witness in the case.

The movie doesn’t provide a sympathetic portrait of either of its leading men, much like Jager’s book doesn’t. Le Gris portrays himself as the Lancelot to Marguerite’s Guinevere, saving her from an unpleasant marriage, whereas Carrouges sees himself as a brave knight protecting his wife’s honour.

The true nature of the men’s characters only becomes apparent in the film’s concluding scene, when Marguerite is given the opportunity to speak for herself: Carrouges, a “jealous and combative man,” as described by Jager, is primarily focused on preserving his own ego.

Le Gris, “a large and powerful man” with a reputation for womanising, is too conceited to see the unwelcome nature of his advances and too self-assured to think that Marguerite will carry out her threat to seek retribution after the act is done.

A representative informs Marguerite in the movie’s trailer, “The punishment for giving false testimony is that you are to be burned alive.” She replies, teary-eyed but resolute, “I will not be silent.”

The movie’s various perspectives highlight how difficult it was to know the truth about Marguerite’s case, which split observers both at the time and over the years.

Some said that she had implicated Le Gris unjustly, either by mistaking him for someone else or by acting at her vengeful husband’s direction.

Diderot and Voltaire, two enlightenment philosophers who opposed Le Gris’ “barbaric and unjust trial by battle” as an illustration of “the imagined stupidity and savagery of the Middle Ages,” supported Le Gris’ case, according to Jager.

This idea was repeated in other encyclopaedia entries, which seemed to confirm Le Gris’ guilt.

For his part, Jager tells Medievalists.net that “if I had not believed Marguerite,” he “never would have begun on writing this book.” Jean Le Coq, Le Gris’ attorney, may have best summed up the situation when he wrote in his journal that “no one actually knew the facts of the matter.”

What incidents is The Last Duel a dramatisation of?

Born into a high-born Norman family in the 1330s, Carrouges met Le Gris while both were serving as vassals to Count Pierre. Le Gris was a lower-born man who progressed through the ranks due to his own political acumen.

They had a close relationship that soured when the count showered Le Gris with generous presents of money and territory, inciting Carrouges’ envy. The once-friends developed a fierce animosity that was fueled by Carrouges’ numerous unsuccessful legal arguments.

Carrouges and Marguerite first met Le Gris in 1384 while attending a friend’s party. The men welcomed each other and gave each other a bear hug after appearing to put their issues behind them. Carrouges instructed Marguerite to kiss Le Gris “as a show of renewed peace and friendship,” according to Jager.

The occasion served as the setting for the first encounter between Le Gris and Carrouges’ wife, who was described as “beautiful, good, sensible, and modest” by a contemporary chronicler. The two guys were in their late 50s at this point, making Damon almost exactly the appropriate age for the part but Driver a good generation off.

It’s uncertain whether Carrouges and Le Gris genuinely reconciled at this time. But Marguerite undoubtedly left an impression on Le Gris, who probably still harboured animosity for his litigious old friend: In January 1386, after meeting the freshly knighted Carrouges, Le Gris dispatched Adam Louvel, a fellow courtier, to watch over Marguerite, who had been left behind with her mother-in-law while Carrouges journeyed to Paris.

All that was lacking for Le Gris at this point was an opportunity, as Jager puts it: “With a motivation, revenge against the knight, and a means, the seduction of his wife.”